11.10.18

CQC: ‘Postcode lottery’ makes way for ‘integration lottery’ as NHS walks towards ‘unjust’ future

This year’s CQC State of Care report has found that most people in England receive a good quality of care, but that, much like the situation last year, quality remains inconsistent and access to care is very much dependent on where you live.

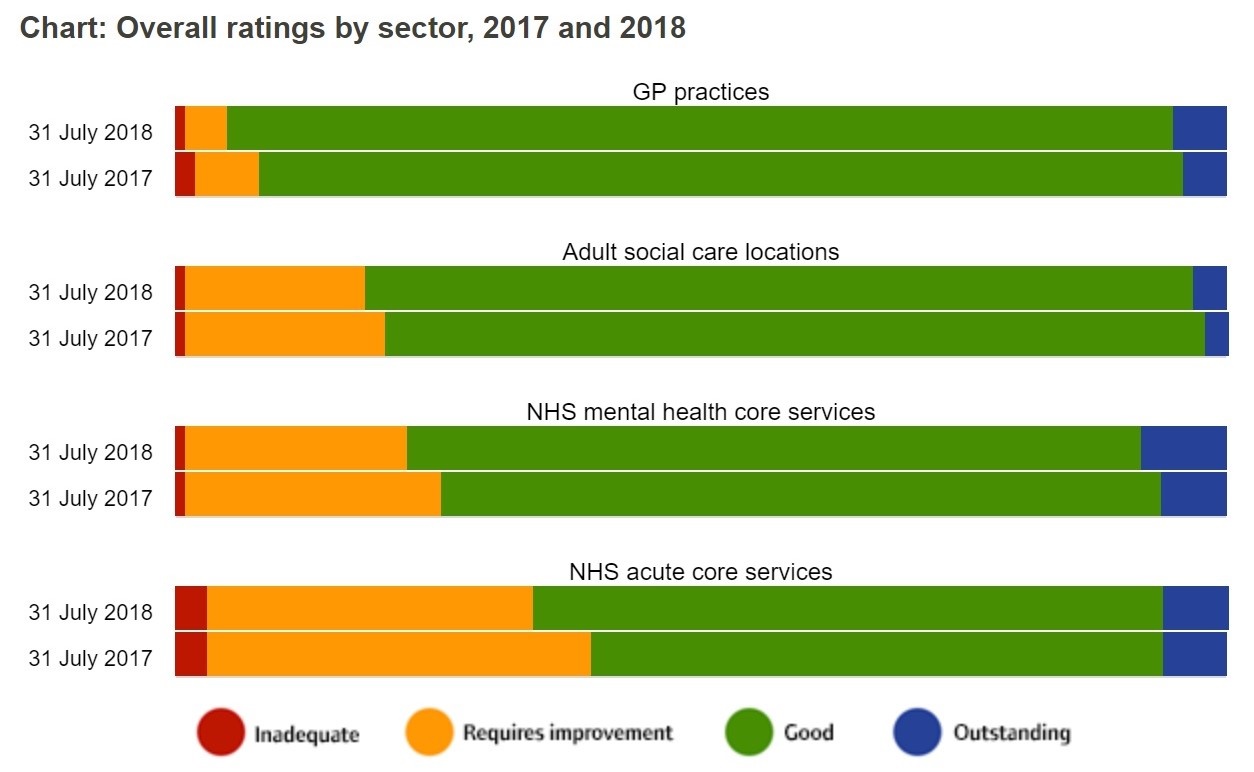

The CQC’s ratings showed that since last year, quality of care has generally been maintained and, in some areas, improved – which the inspectorate puts down to the hard work of care staff, despite the many challenges faced by providers.

But this wasn’t the case everywhere, and access to this good-quality care increasingly depends on where in the country you live and how well an area works together as a system.

A future of ‘care injustice’

Ian Trenholm, chief executive of the CQC, said the findings highlight not so much a ‘postcode lottery’ but an ‘integration lottery,’ with quality directly linked to the health and care system as a whole.

He argued that there must be incentives to bring local health and care leaders together rather than drive them apart – which, in practice, could mean changes to funding to allow services to pool resources. This could then lead to greater investment in vital technology, such as digital monitoring devices, e-prescribing, and electronic immediate discharge summaries.

“The challenge for Parliament, national and local leaders and providers is to change the way services are funded, the way they work together and how and where people are cared for and supported,” continued Trenholm.

“The alternative is a future in which care injustice will increase and where some people will be failed by the services that are meant to support them, with their health and quality of life suffering as result.”

The report identified five key areas that affect the sustainability of good care.

Access

Quality of care is not consistent across the country and some people are unable to access the services they need because of where they live, meaning that for some the only service they can reasonably access may not be adequate.

The report found that there are nearly one and a half million older people who do not have access to the care they need, and the people who access mental health services often have to travel long distances to do so.

One person told the CQC: “I got an appointment with a psychiatrist within a month of going… that was brilliant. Three days before my appointment, the psychiatrist left. I was put on the waiting list and I’m still on the waiting list.”

Quality

The overall quality of care has slightly improved since last year, but there are still too many people who are not receiving good care. The CQC said that the safety of people using care services remains its biggest concern, and while there have been improvements in this area across social care and GP services, smaller improvements are still needed in acute hospitals and mental health services.

According to the report, GP practices seem to have the best rating when it comes to quality of care, with 96% considered either ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’ compared to 93% last year – whereas 31% of NHS acute core services are still rated as ‘requires improvement.’

Workforce

The report acknowledged that the care sector is struggling to recruit, retain and develop the right staff, noting that there are 110,000 vacancies in adult social care.

A lack of care staff was the most common reason children and young people had delays in accessing mental health services, and recurring and retaining GPs is problematic in an ageing workforce.

One person told the CQC that most staff are temporary and are on six-month or one-year contracts, so they don’t get training – or, when they do, “by the time they know anything, they’re gone.”

Another person said: “You can see the impact when one member of staff is unable to come in – you can see a ripple right across the system. It doesn’t matter if it’s a nurse or a consultant – if there’s someone missing you can see the impact this has...”

Demand and capacity

“The mental health services in this area are completely shot. There’s too much for them to do. There aren’t enough people to cope with the patients, it’s totally wrong,” the CQC was told.

Demand for care services is rising because of an ageing population and a rise in the amount of people living with chronic or multiple conditions, and so providers face the challenge of finding the right capacity to meet people’s needs

The CQC therefore recommends that services need to work and plan together to meet the need of local populations and prepare for peak periods such as winter.

Funding

Despite the NHS getting its £20bn long-term funding boost, there has been no similar arrangement for social care, so care funding and commissioning structures will be essential in helping drive improvement. But health secretary Matt Hancock did announce earlier this month a £240m emergency injection for social care to help free up beds this winter.

The CQC report also found that there is variation in how care homes are funded across England: 46% of care homes in the South West are self-funded, compared with 23% in the north east.

Enjoying NHE? Subscribe here to receive our weekly news updates or click here to receive a copy of the magazine!