Back in January 2019, Richard Whittington, then Assistant Director of Commissioning, now Chief Executive of Local Optical Committee Support Unit, wrote a blog for the NHS England (NHSE) website. Entitled Creating a Community of Care on Eye Health, it made interesting reading then and resonates as firmly now during these challenging times for the NHS.

In January 2021, 604,401 were waiting for a first treatment in ophthalmology, 230,872 have waited more than 18 weeks and 48,703 have waited more than a year.

Richard’s central point was that optical professionals are a key asset in protecting and transforming the health outcomes of citizens; assessing someone’s ocular function and acuity can discover more than just a need for spectacles. Hitherto undiagnosed disease can be detected, and an earlier intervention will bring better outcomes. Certainly, with the work that Conclusio has carried out in this field, now is the time to ensure the experts are given a platform to drive change across a whole system of care.

Despite this, optical clinicians and their teams are often neglected in the scheme of multi-disciplinary team working and fail to be recognised as frontline health professionals; a phenomenon experienced by other groups of health professionals. During our development of the National 10-Point Plan for the Management of Malnutrition – Feeding Better Outcomes, similar experiences were expressed by nutrition professionals within multi-disciplinary health care systems. Put simply, they did not enjoy the status they deserved and, as a result, their fullest value in integrated care and system-wide approaches was not being optimised.

Optical professionals, working in the community, do so largely on the same streets as another health and social asset that has often faced status issues. Community Pharmacy, just as optical professionals do more than sell spectacles, does more than dispense pills. Yet, while it has had to struggle to assert its place, it is now instrumental in the system leadership that is demanded as a result of the NHS Long Term Plan and the spawning of Integrated Care Systems. In London, Local Pharmaceutical Committees (LPCs) have driven forward a community pharmacy strategy, which determines a new service offer. There is significant value to be drawn down through an integrated care pathway, where community optometrists are working hand-in-glove with consultant ophthalmologists. However, relationships between any co-professionals only prosper where dialogue is supported that drives parity of esteem across all health professionals involved in the achieving of better outcomes for patients.

The recently published Government white paper, Integration and innovation: working together to improve health and social care for all, is a “blueprint” for “stripping away unnecessary legislative bureaucracy, empowering local leaders and services and tackling health inequalities.”

This builds on the NHS’s Long Term Plan proposals and is set to accelerate the rate of integration across the NHS, making the case – as stated in the recent white paper “…for joining up and integrating care around people rather than around institutional silos – care that focuses not just on treating particular conditions, but also on lifestyles, on healthy behaviours, prevention and helping people live more independent lives for longer. We need the different parts of our health and care system to work together to provide high quality health and care, so that we live longer, healthier, active and more independent lives”

This person-centred focus extends its lens into the working approaches and arrangements for, and between, health care professionals. The White Paper further highlights “…the brilliance of our doctors, nurses, carers and other healthcare professionals in providing world-class care to those in need. What has gone unseen by many is that in order to provide this level of care the traditional dividing lines between health professionals have been cast aside to allow unprecedented levels of collaboration.”

Dividing lines being painted out of the picture, walls coming down and silos being opened up; admirable and much needed actions but inter-health professional status has to be assured too. True shared decision making on how to plan, build, deliver and measure optimum care requires all the care professionals involved to view each other as equals.

The concept and practice of integration crops up regularly in the dynamics of professional status and esteem. Returning to the blogs on the NHSE website, a few months on and there was an interesting post from Professor Amy Edmondson of Harvard Business School. An expert on ‘teaming’ she outlined a four-part approach to building teams that can help increase success. Taken from her recommendations Extreme teaming. How to deliver integrated care, Professor Edmondson cites:

- Aim High. Set a clear, ambitious, and meaningful vision which inspires people by focusing on the humanity of the work – the things that matter to us, not some business process or performance indicator – and aligns their effort around that goal.

- Team up. Bring together the right mix of people for your project. A homogenous team may have greater chance of success in routine tasks, but diverse teams have the ability to achieve breakthroughs by creating the synergies to innovate.

- Fail well. Identify opportunities for intelligent failures that provide information on how to improve approaches and systems. The point at which the system breaks down will often be the greatest opportunity to learn.

- Learn fast. Maximising learning requires focus, discipline and structure when reviewing failures. The US Army uses four simple ‘action review questions’: What did we intend to do? What actually happened? What is the difference and why? What will we do the same and what will we do differently next time?

What are the implications and pointers in this for the optical health community? Finding a common cause is a good starting point. In the current climate of COVID-19 restrictions, the associated impacts on health and wellbeing in the population, and the consequences for our health systems, looking at a care pathway that is under strain is a good jumping-off point.

Glaucoma as a group of eye conditions is one of the most common causes of blindness worldwide. In the UK about two per cent of the population over 40 have the condition and by 2035, the number of people living with glaucoma in the UK is expected to increase by 44%.

While much of the diagnosis of glaucoma in the pathway resides in secondary care, there is a growing consensus, GIRFT16 & NICE17, that more of the risk stratification and management needs to be done in the community. For many years there have been designs to expand the provision of care in local communities. The NHS Long Term Plan set objectives for that with out-of-hospital models and an overarching plan to avoid admissions.

Issues that were once barriers to getting services out of Trusts and into the community, have started to fall. It provides an opportunity for optical clinicians and their teams to unite around an issue and assert their place in a glaucoma optimal care pathway.

Though the barriers might be lower, culture, custom and practice can be stubborn agents to remove. To understand why outmoded behaviours might persist in the existing pathway approach, and how the optical health community can navigate them – and in so doing show clinical leadership – we need to examine some of the drivers that until now have set the tone.

- NHS financial regime. Payment by results, the tariff system of money following patients has meant secondary care has not been induced to letting patients go.

- Professional to professional dynamics. Parity of esteem and the assumption of vested interests can be a barrier.

- The ‘too difficult’ pile. Changing services delivered by hospitals is at the top of the managerial ‘avoid at all costs’ due to a fear of patient-backlash.

- Public perception. Hospital might be the right place for patients with an acute need but anything else, community is best.

- Care silos. Care systems have historically been disjointed with the result that patients get a poor experience when crossing the ‘boundaries’ between different parts of the system.

- Restrictive practices. The protection of rigid boundaries between professional groups.

However, things have shifted. The financial regime has been turned on its head, block contracts are altering the motivations of hospital leaders. Covid-19 has necessitated reduced hospital footfalls and many of those resistant to change, have been persuaded to align. The development of Integrated Care Systems has accelerated joined up working. An important emerging development is the place of accountability; incentive and sanction are now at system level.

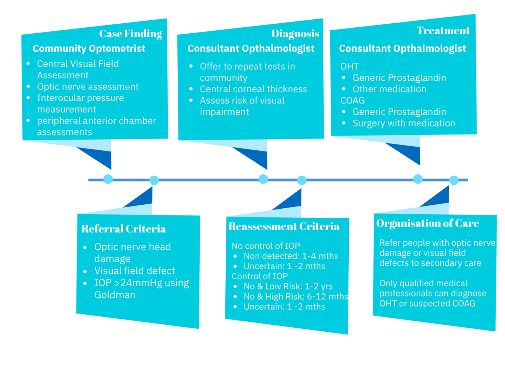

All this shows good prevailing conditions to steer optimal care through the community. Given that waiting lists for glaucoma treatment might very well be keeping a lot of trust CEOs awake at night, this presents another opportunity to state the case for community care. The NICE NG81 guidelines refer and are illustrated in the following table:

Source: Glaucoma: diagnosis and management NICE guideline [NG81] Published date: 01 November 2017

It is clear that there is a powerful body of evidence for galvanising the strength of offer in community optometry in delivering within an optimal glaucoma care pathway. From diagnosis to follow-up care, care in community settings will provide a better experience for patients, strengthen to role of community optical clinicians and better serve the objectives of integrated care.

The recent NHSX allocation of £8.5m funding across England’s seven NHS regions for technologies that allow hospital ophthalmologists to access records, referrals and diagnostic images from high street optometrists, will bring community optometrists within real-time reach of secondary care clinicians and support the sharing of diagnostic images and streamline referrals. This will allow optometrists to consult with clinicians in real-time, share diagnostic images, and refer patients to hospital, and forming part of a much-needed infrastructure for optimising integrated glaucoma care in the community.

Just as Government is directing increased integration in the NHS, the draft ABPI Code of Practice 2021 seeks to align Pharma with the proposed new approaches. It sets the ground for Pharma to partner with the NHS with true purpose. On collaborative working it gives clear licence and legitimacy for Pharma to place itself at the centre of transformation and optimal care planning. On joint working it creates the ground on which meaningful patient-centric partnerships can flourish and drive better health outcomes. Together, this supports ‘above brand’ working and sets the tone for, and direction of, multiple entities (statutory and commercial) engaging in a commonwealth for common health.

While there is not a register of people who might be good candidates for better outcomes from an optimal care pathway to support unmet need, the focus must remain on not precipitating inequalities in prescribing of Glaucoma medications. We need an optimal care pathway to collect the data to help address unmet need and inequalities through interventions that are based on shared decision making between patients and health care professionals alike. Pharma companies like AbbVie are starting to engage with these challenges and see themselves as potential partners of the NHS in a purposive approach to addressing these kinds of challenges.

Changes in the NHS landscape, the delivery of care and the Covid-19 pandemic have taught many things to all those engaged in providing quality patient care. A clear opportunity to act exists; everyone needs to change their mind-set and demonstrate a commitment to work in partnership across the whole healthcare system. Adopting shared goals that move us away from silo leadership and thinking and deliver more positive outcomes rather than just more barriers.

Written by James Skillicorn-Aston and Mike Proctor

Find out more by visiting www.conclusio.co.uk or emailing Conclusio at: [email protected]