Immune cells could help clinicians improve cancer care and design better treatments, new research has revealed.

A study, conducted by King’s College London, Guy’s and St Thomas' and the Francis Crick Institute, analysed 127 patients with skin cancer and found a rare type of T cell can help predict which patients would benefit most from immunotherapy treatments.

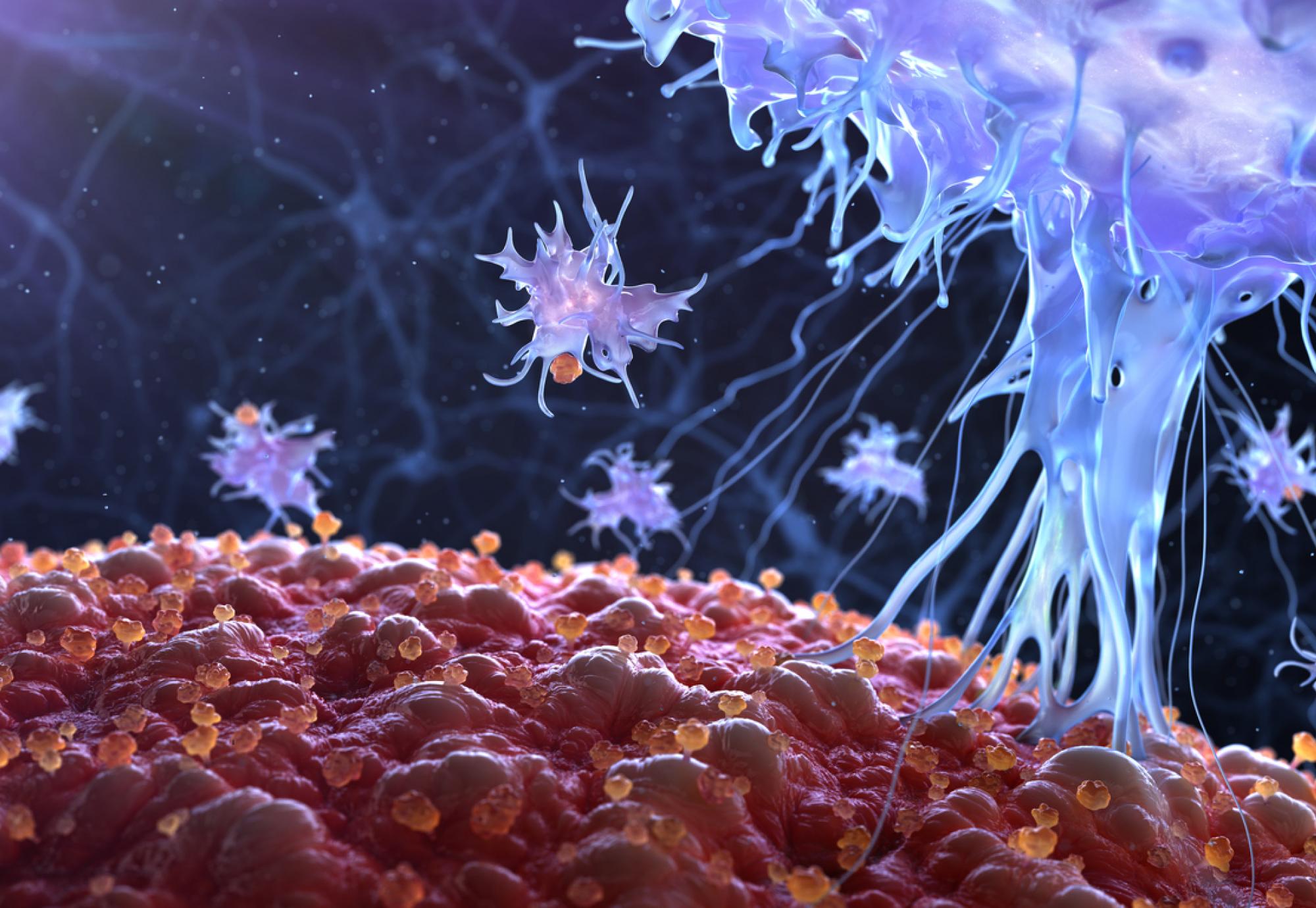

When attacking the body, cancer can suppress certain proteins on immune cells that would normally attack it.

However, a type of immunotherapy treatment known as immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) has been shown to be able to reactivate these immune cells, allowing them to target cancer cells by recognising mutations not present in healthy cells.

Dr Yin Wu, co-senior author of the report, explained: “The number of cancer mutations can sometimes help doctors identify the patients most likely to benefit from ICI therapy but curiously, some cancers with very few mutations can still respond very well.

“Our research team reasoned that these successes must be due to other immune cells that can see cancer cells even in the absence of lots of mutations.”

A rare type of T cell (Vd1-gd T cells) can identify and kill cancer cells without needing mutations to find them – these cells are inside tumours when there is also a specific type of immune checkpoint protein called PD-1.

After analysing patients with melanoma who were treated with the ICIs that targeted PD-1, researchers found that the presence of Vd1-gd T cells had a high correlation with positive responses to therapy – especially in cancer with few mutations.

The researchers then used a new technique to isolate and grow these cells from human tissues, which enabled them to show, for the first time, that Vd1-gd T cells can be reactivated by the ICI therapies used by the NHS to treat skin cancer patients.

Dr Shraddha Kamdar, a research fellow at King’s and co-first author, said: “The study findings may help doctors decide which patients are most likely to benefit from current immunotherapies.

“These therapies are both costly and importantly can cause severe and life-long side effects, so it is important to be able to predict when they will actually work.”

The study also observed that Vd1-gd T cells demonstrated higher levels of resistance to attacks from cancer cells than more common forms of T cells.

Ultimately, the findings can help the NHS decide which patients would benefit most from immunotherapy treatments, avoiding unnecessary patient exposure to side effects and the cost of treatments that are not effective.

Professor of immunobiology at King’s and principal group leaders at the Francis Crick Institute, Adrian Hayday, explained: “Collaboration is key to any scientific study, and this project shows the benefit of working together across institutions.”

Prof Hayday, who is co-senior author of the research, continued: “The study’s results are striking, and strongly support ongoing efforts to directly infuse Vd1-gd T cells into patients with cancer, an approach pioneered at King’s College London and the Francis Crick Institute.”

Image credit: iStock